CMS is asking infusion providers to submit comments about selected drugs as part of the Medicare Drug Price Negotiation Program. This includes the first negotiations for Part B drugs under the program.

This is an opportunity to help CMS better understand that community-based infusion providers operate on thin margins, and changes to reimbursement could threaten the ability to safely deliver Part B therapies.

Starting in 2028, Medicare plans to reimburse selected Part B drugs using Maximum Fair Price (MFP) + 6%, instead of the current ASP + 6% model. CMS has also indicated it will include MFP in the ASP calculation, which would drive down reimbursement beyond Medicare and impact the commercial market as well.

CMS needs to hear directly from providers who understand buy-and-bill, patient access barriers, and real-world site-of-care dynamics.

Note: This resource is provided for informational and advocacy purposes only and does not constitute legal or regulatory advice. This guide focuses on access and reimbursement impacts. Providers should respond to the clinical aspects of survey questions using their own professional judgment and experience. Providers are encouraged to submit comments based on their individual clinical and operational experience.

Submit comments here by March 1, 2026.

Additional step-by-step guide on accessing the survey.

Questions? Contact [email protected]

What are the goals of treatment for the condition(s) treated by the selected drug?

You may want to include:

- Achieving remission or low disease activity

- Preventing disease progression and irreversible damage

- Reducing flare-ups and acute episodes

- Avoiding hospitalizations and emergency department visits

- Improving patient function and quality of life

- Supporting the ability to work, attend school, and care for family

- Maintaining long-term stability on the right therapy

Suggested framing:

- “Treatment goals depend on continuity of care. Delays, changes in site of care, or forced non-medical switching can reverse progress.”

Are there widely used evidence-based clinical practice guidelines?

Providers may cite relevant specialty society guidelines depending on the drug and indication (examples: gastroenterology, rheumatology, pulmonology, oncology).

You may want to emphasize:

- Switching stable patients for non-medical reasons is not evidence-based

Suggested framing:

- “Clinical guidelines support individualized care. Payer-driven barriers often interfere with guideline-based treatment.”

How does the selected drug fit into the current treatment paradigm?

This is your opportunity to describe where the drug fits in real-world practice.

You may want to include:

- First-line vs. second-line positioning

- Use in moderate-to-severe disease

- Use in patients who have failed conventional therapies

- Role as maintenance therapy

- Importance of infusion/injection delivery for adherence and monitoring

Key message:

- “This drug is often used for patients who require stable, long-term therapy and close monitoring.”

At what point in treatment might the selected drug be considered?

CMS is asking about when and why a drug is used. This is an opportunity to explain that this can be influenced by both clinical guidelines and insurer requirements.

You may want to include:

- Use after failure of conventional agents

- Use after inadequate response to other biologics

- Use based on comorbidities, contraindications, or safety concerns

- Use based on patient characteristics and prior response history

- Use after insurer-mandated step therapy requirements have been satisfied, even when earlier access may have been clinically appropriate

What medications would you consider to be potential therapeutic alternatives?

Providers can list alternatives, but may note that biologics and biosimilars are complex drugs, and therapeutic alternatives are not always clinically interchangeable for individual patients. Providers may also wish to explain that switching stable patients can lead to loss of response, disease flare, or adverse events, particularly when changes are driven by formulary design rather than medical necessity.

Key message:

- “Alternatives exist, but patients are not interchangeable. Switching a stable patient is not risk-free.”

What considerations drive treatment selection among the selected drug and its alternatives?

This is an opportunity to describe the real factors that influence treatment decisions, both clinical- and insurer-related.

In terms of insurer considerations, providers may include:

- Formulary placement and tiering

- Prior authorization requirements

- Step therapy requirements

- Non-medical switching risk

- Patient cost-sharing and coinsurance

- PBM-driven formulary decisions

Suggested message:

- “Insurance requirements (step therapy, non-medical switching, etc.) can override or delay clinical decision-making.”

Are there notable differences between how these drugs are used in your practice versus broader guidelines?

This is a great place to describe how payer rules shape care.

You may want to mention:

- Step therapy delays impacting guideline-based escalation

- Non-medical switching disrupting stable patients

- Formulary instability year to year

- Excessive administrative burden for prior authorizations

- Peer-to-peer and appeals consuming clinical staff time

- Delays in initiation or continuation of therapy

Suggested framing:

- “Real-world practice is heavily shaped by utilization management, not by clinical guidelines.”

What insurance coverage or access issues do patients experience?

This is one of the most important questions. Providers should highlight real-world barriers that delay care and increase risk.

Providers may include:

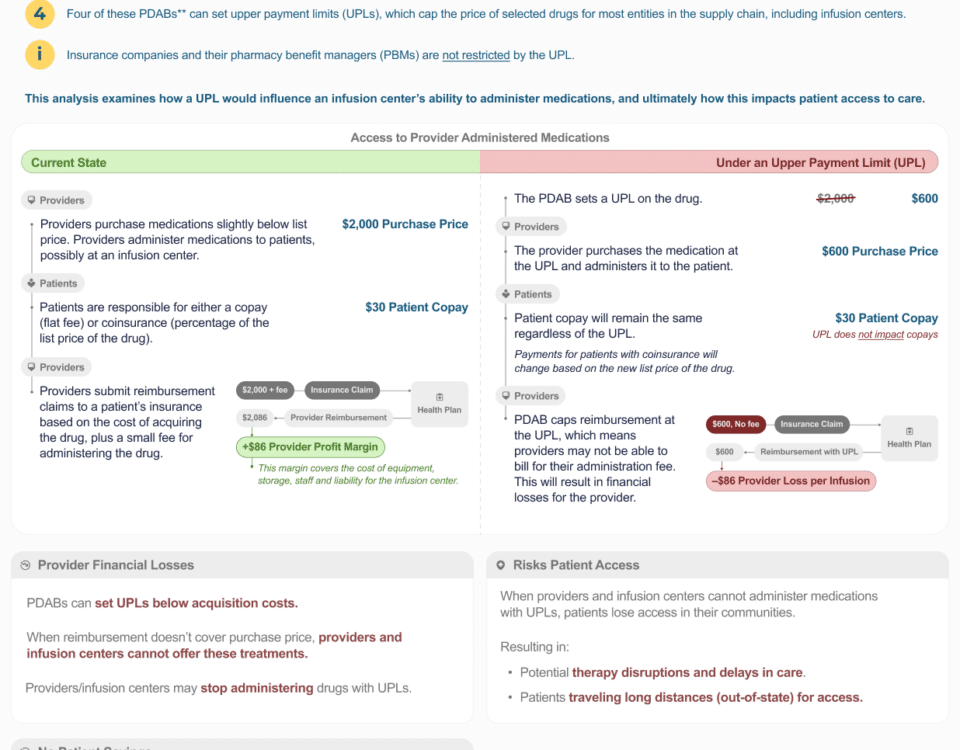

Maximum Fair Price (MFP) and Reimbursement Changes (Pricing Caps)

Providers may want to explain that:

- Community infusion centers rely on the ASP + 6% add-on payment to cover acquisition and operational costs under the buy-and-bill model

- Reimbursement tied to MFP could fall below provider acquisition costs, putting providers “underwater” financially

- If infusion centers are forced to stop offering certain drugs due to reimbursement shortfalls, patient access could be disrupted

- Reduced community infusion capacity might contribute to patients receiving more care in hospital outpatient departments, which could increase overall cost of care and patient cost-sharing

- These reimbursement reductions may worsen access even if the policy is intended to improve affordability

Example:

- “If reimbursement does not cover the cost of acquiring and administering these therapies, patients could lose access to community-based infusion sites and may be forced into higher-cost settings.”

Step Therapy (“Fail First”)

Step therapy is when insurers require a patient to try and fail another medication before the provider-prescribed treatment.

This can delay appropriate care and worsen outcomes.

Example:

- “Step therapy delays initiation of medically necessary treatment and increases the likelihood of flares and complications.”

Non-Medical Switching

Non-medical switching is when insurers force stable patients to change medications for financial or formulary reasons.

Example:

- “Patients who are stable may be forced to switch due to formulary changes, putting disease control at risk.”

Prior Authorization

Prior authorization is the insurer approval process required before treatment can begin or continue.

Providers may describe:

- weeks-long delays

- repeated paperwork

- peer-to-peer reviews

- appeals processes

Example:

- “Prior authorization delays can cause missed infusion appointments and clinical deterioration.”

Copay Accumulators and Maximizers

These programs prevent manufacturer copay assistance from counting toward the patient’s deductible or out-of-pocket maximum.

Providers may highlight:

- surprise bills

- treatment abandonment

- financial distress

Example:

- “Patients may think treatment is affordable, then face unexpected costs mid-year.”

PBM Influence

PBMs control formularies and negotiate rebates that may influence which drugs are preferred.

Providers may emphasize:

- formulary placement does not always reflect clinical best practice

- patient cost-sharing may remain high even when reimbursement changes

Site-of-Care Steering and White Bagging

Providers may describe:

- payer requirements forcing patients into hospital outpatient departments

- restrictions on community infusion

- payers forcing patients to obtain their medication from a specialty pharmacy instead of their infusion provider (threatening buy-and-bill)

Key message:

- This increases total cost of care and disrupts continuity.

What else should CMS consider?

This is where providers should reinforce the biggest risk of the MDPNP expansion.

Providers may emphasize:

A. Provider reimbursement stability is essential for patient access

Community infusion centers rely on ASP + 6% reimbursement under buy-and-bill. Shifting reimbursement to MFP + 6% may reduce add-on payments and threaten the ability to safely deliver Part B therapies.

B. Including MFP in ASP calculations could harm the commercial market

CMS has indicated that MFP will be incorporated into ASP calculations, which would reduce reimbursement beyond Medicare and create a broader market impact.

C. Providers cannot be forced to float costs

Models that require retrospective reimbursement or delayed payment create financial hardship and administrative burden for providers operating on thin margins.

D. If community infusion centers close, patients will be pushed into higher-cost settings

Loss of community infusion access would likely shift care to hospital outpatient departments, increasing total cost of care and increasing patient cost-sharing.

E. CMS must address utilization management barriers

Even if negotiated prices reduce Medicare spending, patients may not benefit if plans increase:

- prior authorization

- step therapy

- non-medical switching

- tier manipulation and high coinsurance

Plans can still keep these therapies out of reach for patients.

F. Stable patients should not be destabilized

Continuity of care is essential for chronic, progressive conditions. Forced switching or delayed treatment can lead to disease progression, hospitalization, and irreversible harm.

Register for a CMS Patient Roundtable Event

Registration Deadline: March 6, 2026

Roundtable participation is open to patients, caregivers, and patient advocacy organizations. Selected participants will receive a confirmation email the week of March 9, 2026, and will have four business days to confirm participation and request accommodations if needed.

Roundtable dates: April 6–17, 2026 (drug-specific sessions):

- Anoro Ellipta: Monday, April 6 from 11 a.m. – 1 p.m. ET

- Biktarvy: Monday, April 6 from 2:30 – 4:30 p.m. ET

- Botox; Botox Cosmetic: Wednesday, April 8 from 11 a.m. – 1 p.m. ET

- Cimzia: Wednesday, April 8 from 2:30 – 4:30 p.m. ET

- Cosentyx: Thursday, April 9 from 11 a.m. – 1 p.m. ET

- Entyvio: Thursday, April 9 from 2:30 – 4:30 p.m. ET

- Erleada: Friday, April 10 from 12 – 2 p.m. ET

- Kisqali: Monday, April 13 from 11 a.m. – 1 p.m. ET

- Lenvima: Monday, April 13 from 2:30 – 4:30 p.m. ET

- Orencia: Tuesday, April 14 from 11 a.m. – 1 p.m. ET

- Rexulti: Tuesday, April 14 from 2:30 – 4:30 p.m. ET

- Trulicity: Wednesday, April 15 from 11 a.m. – 1 p.m. ET

- Verzenio: Wednesday, April 15 from 2:30 – 4:30 p.m. ET

- Xeljanz; Xeljanz XR: Thursday, April 16 from 11 a.m. – 1 p.m. ET

- Xolair: Thursday, April 16 from 2:30 – 4:30 p.m. ET

- Tradjenta: Friday, April 17 from 12 – 2 p.m. ET