Kaitey Morgan, RN, BSN, CRNI, NICA’s Chief Clinical Officer, wrote an insightful post for The WeInfuse IV Insights Blog regarding the importance of thorough clinical documentation and best practices.

As the saying goes: if it wasn’t documented, it wasn’t done. This mantra is instilled in nurses throughout our education and training, and for good reason. Clear, accurate, timely documentation in the medical record, whether electronic or—gasp!—paper, is an essential component of patient care in all settings, as it provides a lasting snapshot of each encounter.

In a field as unique as infusion therapy, there are certain aspects of documentation that warrant special consideration. The billing aspect of infusion documentation gets a lot of attention; after all, if it wasn’t documented, it wasn’t done, and you won’t be getting paid for it. But what about conversations had in passing, or the quick “doorway assessments” that often don’t make it into the chart? In the event that a patient has an adverse outcome during or after the visit—maybe years after— meticulous documentation is often the deciding factor between implication and exoneration.

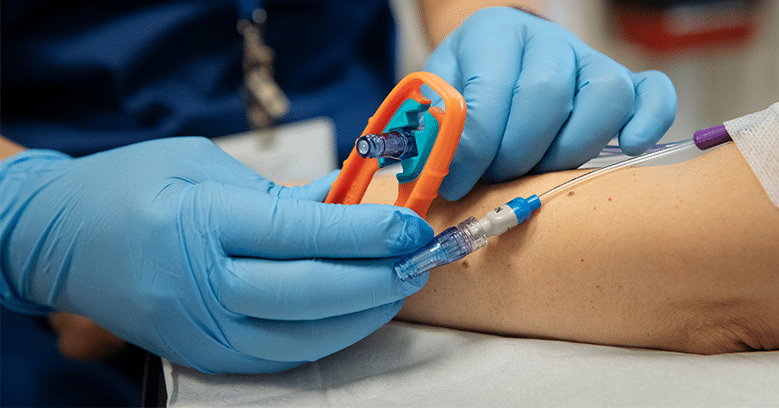

Let’s say a patient files a lawsuit claiming that they experienced numbness and tingling after you placed their IV for an infusion. The suit alleges that the patient told you about these symptoms, and according to the patient you told him it was normal and not to worry. In the months that followed, the patient experienced increasing pain and numbness, and progressively lost range of motion to the point of permanent disability. You are now called to defend yourself, three years later. Having no recollection of the patient or alleged incident, you rely on your nursing notes which read: “IV placed in L wrist on 3rd attempt.” Based on this documentation, how confident would you be in your ability to successfully defend yourself against these claims? What would a jury think of this note? It makes no mention of the number of attempts, catheter gauge, location, functionality, site appearance, or how the patient responded to the procedure—all of which are required per infusion nursing standards, and are especially relevant given the patient’s claims.

This scenario comes from a real case brought against a nurse working in an outpatient surgery center, and the plaintiff received a $375,000 settlement. Here’s the kicker; a month prior to the IV incident in question, the patient had a carpal tunnel release performed on that left wrist. Following the IV incident, the patient’s hand surgeon diagnosed nerve damage which was felt to be associated with the carpal tunnel release. One would imagine that the hand surgeon’s testimony would be the smoking gun, allowing the nurse to successfully defend herself; after all, there is ample evidence that the patient’s symptoms are related to his history of carpal tunnel syndrome and not the nursing care he received a month later. So why didn’t the nurse want this case to go to trial? Dubious documentation.

The patient claimed that three nurses made a total of seven attempts to ultimately place the IV, however the defendant only documented three attempts and did not include any mention of other nurses’ attempts (though the patient had photographs and a witness to support his version of events). Between the poor documentation and the length of time that had gone by, none of the nurses involved could remember who ultimately managed to successfully place the IV.

The medical record also did not contain notes about the patient’s complaint of numbness and tingling or the nurse’s response to the complaint. Even though defense experts were able to refute claims that the IV placement failed to meet the standard or caused the patient’s disability, the inaccurate documentation was alleged to represent a breach in the nursing standard of care—and also called the nurse’s overall competence into question. For these reasons, legal counsel felt that a jury trial would not be in the defendant’s best interests and settled.

So, what can you do to help avoid finding yourself in this nurse’s shoes?

- Take documentation as seriously as patient care. You wouldn’t risk your patients’ safety by cutting corners in any other aspect of nursing care, so don’t rush through charting your excellent care either.

- Take credit for all of the care you provide. Nurses are such skilled multi-taskers that we perform assessments within assessments without even realizing it. If you check on a patient and your documentation only shows the set of vital signs you recorded, that probably doesn’t tell the whole picture. I am willing to bet that while you were there, you also looked for evidence of a reaction like flushing or hives, assessed the IV site for leaking, swelling, redness or pain, and maybe asked about the presence of complaints like shortness of breath or headache. You did it, so chart it!

- Only take credit for the care you provide. We have all had this happen– a coworker helps you out by placing an IV in your patient, but for one reason or another does not document it before leaving for the day. Ideally your coworker should document it at their earliest opportunity, even if it is the next day (in that case, the note should be labeled as a late entry), but life happens. As the patient’s primary nurse, you should ensure the record is complete and accurate by attributing the placement to your colleague in your documentation of the site (because you should still record your own assessment before using the IV!).

- Develop comprehensive, evidence-based policies—and follow them. Sometimes policies get a bad rap for being impractical, rigid documents that make a hard job harder, but I love a good policy and you should too! A well-crafted policy should serve as an easy-to-follow reference to guide proper care according to established standards, rather than a tool to audit conformity afterwards.

- Make it easy to do it right. A facility may have a top-notch gold-star-worthy documentation policy, but if the expectation is that every nurse will remember to include all of the required elements in a narrative note on every patient, every time, compliance rates will be low. The flowsheet should serve as a template to prompt the nurse to record each piece of essential information; this will produce a much more consistent, comprehensive record than relying on memory alone.

Even when nurses do everything right, however, we cannot control every outcome. What we can do, however, is document every assessment, observation, conversation, and intervention so that if a patient has a bad outcome, the legal record reflects the entirety of the encounter and the quality of care provided.

This article was originally published September 29, 2020 on the WeInfuse IV Insights blog. Read the original post here >>