“Humans are not ideally set up to understand logic; they are ideally set up to understand stories.” — Roger C. Schank, Ph.D., cognitive psychologist

Anyone who has worked in healthcare or been a patient—so, everyone—has likely had a frustrating experience trying to coordinate access to care. These experiences leave us shaking our heads, wondering why it is such an uphill battle to get health care to those who need it. Don’t they understand what these seemingly callous rules and restrictions do to patients’ lives? Often, the answer is no, they do not; how would they? They—the decisionmakers and policy-shapers—are isolated from the exhausting, demoralizing, and heartbreaking downstream effects of health policies because they are too far removed from the aftermath. Healthcare providers, however, are at the patient’s side (if only virtually in recent times) and are intimately aware of the ripple effect that follows a denied authorization or a mid-year formulary change. If we expect anyone to understand and consider the true costs of these realities and how they preclude attempts to provide person-centered care, it is our responsibility to share our experiences to help illustrate how ripples turn into tidal waves in real peoples’ lives.

Healthcare providers reading this may now be thinking of all the training modules they have completed over the years stressing the importance of protecting patient’s medical records and other personal health information. How then, can healthcare providers share valuable patient stories without breaching HIPAA regulations or entering the murky ethical waters? To answer this, we can cull guidance for navigating these nuances from the practice of narrative medicine, a relatively new discipline described by its originator Rita Charon, MD, Ph.D., as “a commitment to understanding patients’ lives, caring for the caregivers, and giving a voice to the suffering.” Narrative advocacy is a related subject which promotes sharing of personal stories to advocate for positive change. Where these two fields overlap lies the untapped potential to influence health policy. It is possible to humanize issues using real clinical experiences, while still respecting professional ethics and the principles of confidentiality, privacy, and trust—the cornerstones of the patient-provider relationship.

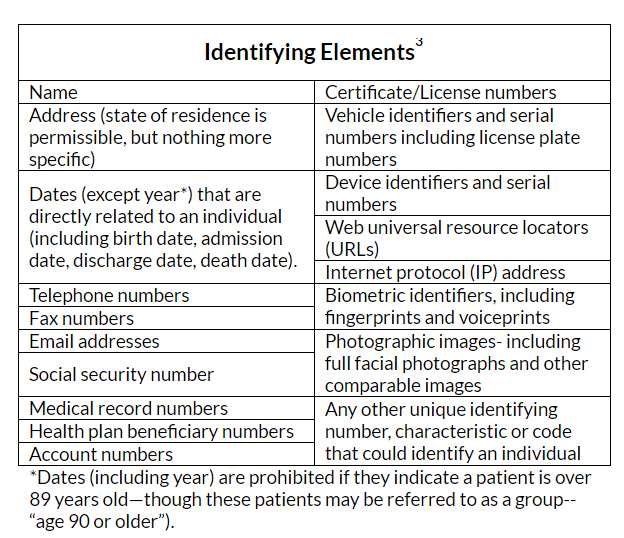

In an ideal world, the storyteller would obtain written authorization from the subject of the story—the patient. An open, honest conversation can help explain that by sharing the struggles they have experienced—or you have experienced together—in getting the care they need, you hope to help prevent others from having to endure the same challenges in the future. If it is not possible to obtain permission (maybe the patient was lost to follow up, moved away, or passed away), their story can still be shared with some extra attention to protecting their privacy. The HIPAA rule considers protected health information (PHI) to be any information that may be used to identify an individual, his/her relatives, employers or household members. The HIPAA rule specifies 18 identifiers which are considered PHI, listed in the table below.

Reading through this list, it seems unlikely that any of these identifying elements are essential to story— but what about the last on the list? What constitutes a “unique identifying characteristic”? This is where the more personal details shared in the telling of a story, which help create color and context, can also reveal a patient’s identity.

It may not seem like a problem to mention a patient’s occupation or hobbies, but in combination with other details, these characteristics may indeed be unique enough to identify the individual. When in doubt about sharing “unique identifying characteristics” ask yourself this: if the patient’s friend or family member read the story, do you believe they would be able to identify the patient? If the answer is “yes”—or even “maybe”—then those details need to be removed or changed.

Imagine that Dr. Jones, a rheumatologist from Dallas, wants to share a story about her patient Mrs. Smith and how an insurance company’s utilization management policies delayed and disrupted her access to care, resulting in disease progression and permanent disability. To convey the profound and personal impact this had on Mrs. Smith, Dr. Jones would like to include in her letter that the patient’s knee pain from rheumatoid arthritis ultimately forced her to give up two things she loved: teaching kindergarten and running marathons. Even if the story was completely deidentified, removing the patient name and any other identifying elements of PHI per HIPAA rules, it is likely that any of Mrs. Smith’s friends, family members or former students would be able to identify her right away based on that description. The story would be just as compelling, however, if instead the subject’s joint pain required her to give up two things she loved: her career and her active lifestyle. Another option Dr. Jones could consider is to replace the more revealing details with fictionalized alternatives that still convey the heart of Mrs. Smith’s experience; after all, the narrative would be just as powerful if it happened in San Antonio to Mr. Smith, forcing him to give up his favorite activities: teaching elementary school and cross-country skiing.

To be clear, providers should not completely fabricate stories and pass them off as truths for the purposes of patient advocacy, however they should tell their real-life stories in a way that protects patients’ privacy with the end goal in mind: highlighting the injustices, inequities and disparities in access to care that threaten the health and well-being of their patients every day. As difficult as it may be, we have to try to put into words the powerless feeling we share with patients as we explain that due to payer policies, the patient will not be able to receive the treatment they need, when they need it, in the setting that makes the most sense for them. If we can empower enough healthcare providers to share these experiences with decisionmakers and policy-shapers, maybe someday we will run out of heartbreaking patient stories to tell.

Kaitey Morgan, RN, BSN, CRNI is NICA’s Director of Quality and Standards. Kaitey oversees the NICA Standards for In-Office Infusion, developing resources and training materials to support NICA’s provider members in their pursuit of clinical excellence. She also collaborates with the team to create patient and provider educational materials and brings a clinical perspective to NICA’s online forums and advocacy efforts.